Home > Auctions > 3 - 11 June 2025

Ancient Art, Antiquities, Books, Natural History & Coins

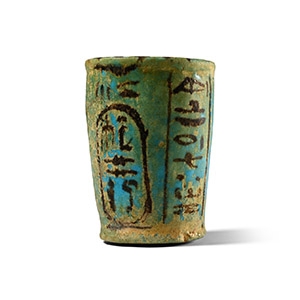

Gunther Markert collection, Germany/Switzerland, 1954 or 1961.

with Robert Bigler, Switzerland.

Private collection, London, UK, acquired from the above on 12 October 2001.

Accompanied by a copy of the Robert Bigler invoice.

This lot has been cleared against the Art Loss Register database, and is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Cf. Andrews, C., Amulets of Ancient Egypt, London, 1994, p. 46, fig. 50, for similar, finely detailed examples.

The Four Sons of Horus were deities tasked with protecting the internal organs of the deceased. The human-headed Imsety safeguarded the liver, the baboon-headed Hapy looked after the lungs, the jackal-headed Duamutef defended the stomach, and the falcon-headed Qebehsenuef protected the intestines. Amulets featuring these deities were included within the mummy wrappings.

Acquired in the 1950-1990s.

Mr C., Geneva, Switzerland.

Private collection, Europe.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by a search certificate number no.12592-232170.

This lot has been cleared against the Art Loss Register database, and is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Cf. Berlev, O. and Hodjash, S., Catalogue of Monuments of Ancient Egypt: From the Museums of the Russian Federation, Ukraine, Bielorussia, Caucasus, Middle Asia and the Baltic States, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 17, Fribourg/Göttingen, 1998, pl. 173, no. XIV.60, for a similar (though less fine) one-piece example.

Winged scarabs were thought to ensure the rebirth and regeneration of the deceased, making them popular funerary amulets. This is a particularly fine example of a rarer one-piece amulet, as they are usually made from three separate elements.

Ex collection of the late Mr S. M., London, UK, 1970-1990s.

This lot is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Phoenician scarabs with winged lions were often used as guardian figures, much like Mesopotamian lamassu or Egyptian sphinxes. On amulets and seals, they likely served as apotropaic (evil-averting) symbols. In Phoenician and Persian art, hybrid creatures like winged lions reflect a cosmopolitan visual language, blending Egyptian, Assyrian, and Achaemenid motifs. They could symbolise imperial power or transcultural authority. In some cases, winged lions are linked to deities or divine guardianship, especially when shown flanking sacred symbols like trees, thrones, or sun discs.

Ex collection of the late Mr S. M., London, UK, 1970-1990s.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by a search certificate number no.12635-234910.

This lot has been cleared against the Art Loss Register database, and is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Cf. Boardman, J., Classical Phoenician Scarabs: A Catalogue and Study, Oxford, 2003, cat. no. 37/18 Tharros pl. 59e (BM ANE 133440), London no. 407, for a similarly-themed motif of a facing bearded head, with an African head to one side over a boar forepart; Boardman, J., 'Greek Gem Engravers, Their Subjects and Style' in Ancient Art in Seals: Essays by Pierre Amiet, Nimet Özgüç, and John Boardman, edited and introduced by Porada, E., Princeton, 1980, 113-114, for discussion.

Grylli motifs usually combine various human and animal heads, sometimes including animal legs.

From the collection of a deceased London gentleman, UK, 1970-1990s.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by a search certificate number no.12636-234419.

This lot has been cleared against the Art Loss Register database, and is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

With Jean-Phillipe Mariaud de Serres, Paris.

Private collection, London, acquired from the above in 1992.

This lot has been cleared against the Art Loss Register database, and is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

with Hoshigaoka Gallery Co. Ltd, Japan.

Private collection, London, acquired from the above on the 26th September 1981.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by a search certificate number no.12637-235085.

This lot is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Acquired in the mid 1980s-1990s.

Private collection, Switzerland, thence by descent.

Private collection, since the late 1990s.

This lot is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Cf. Lacovara, P., Teasley Trope, B., and D’Auria, S.H., The Collector’s Eye: Masterpieces of Egyptian Art from The Thalassic Collection, Ltd., Atlanta, 2001, pp.106-107, no. 59, for an almost identical ring in electrum.

Akhenaten, an 18th Dynasty pharaoh (c. 1353-1336 BCE), introduced a major religious shift by promoting the Aten, the sun disc, as the sole god. Rejecting the traditional polytheistic religion of ancient Egypt, Akhenaten elevated the Aten above all other gods and even changed his name from Amenhotep (IV) to Akhenaten, meaning ‘Effective for the Aten’. He founded a new short-lived capital in Middle Egypt called Akhetaten. However, traditional polytheism was restored after his death, and his reforms were largely reversed.

Ex London and Home Counties collection, UK, 1920-1940.

This lot is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Cf. Ben-Tor, D., The Scarab: A Reflection of Ancient Egypt, Tel Aviv, 1993, pp. 76-77, nos. 1-15, for examples of this type of scarab.

From an early 20th century collection London and Home Counties, UK.

This lot is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Cf. Petrie, W.M.F., Amulets. Illustrated by the Egyptian Collection in University College, London, 1914, pl. I, nos.7a-p, for type; Andrews, C., and van Dijk, J., Objects for Eternity: Egyptian Antiquities from the W. Arnold Meijer Collection, Mainz am Rhein, 2006, p.128, no. 2.34a.

According to ancient Egyptian beliefs, the heart (ib) was considered to be the centre of intelligence, emotions, and behaviour. The heart was also believed to store an individual's memories. During the Weighing of the Heart ceremony in the afterlife, the heart could speak up for the deceased and account for their lifetime of actions before Osiris. For this reason, heart amulets were placed on the mummy to safeguard the organ and ensure a favourable outcome during judgment.

Property of a Surrey lady; acquired by her father Christopher Terry circa 1980.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.12603-233353.

This lot has been cleared against the Art Loss Register database, and is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Cf. Ashour, S., ‘Unpublished Group of Bahnasa Reliefs’ in Archaeological & Historical Studies 13, Alexandria, 2010, pp.65-106, figs.5, 7, for similar stele.

Limestone niches with polychrome representations of the deceased were common in Roman Egypt, and lasted until the time of the Arab conquest. The man depicted on this stele certainly belonged to the high contemporary nobility as is evidenced by his well-pleated clothing, which identifies him as a member of local Graeco-Roman aristocracy.

Belgian private collection, 1950s.

with Christie's, New York, 4 June 2008, no.190.

Private central European collection.

Accompanied by a copy of the relevant Christie's catalogue pages.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by a search certificate number no.12067-218141.

This lot has been cleared against the Art Loss Register database, and is accompanied by an illustrated lot declaration signed by the Head of the Antiquities Department, Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Cf. The Metropolitan Museum, New York, accession numbers 1984.323.2 and 16.140, for similar specimens, in Richter, G. M. A., ‘Recent Accessions of Greek Vases’ in Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 11(12), New York, 1916, pp.255-56, figs.6-7; Metropolitan Museum of Art, ‘One Hundred Fifteenth Annual report of the Trustees for the Fiscal Year July 1, 1984 through June 30, 1985’ in Annual Report of the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1985, no.115, p.38; see also Robinson, E.G.D., Carpenter, T., Lynch, K.M., The Italic People of Ancient Apulia: New Evidence from Pottery for Workshops, Markets, and Customs, Cambridge, 2014, figs.5.2, 6.1.

The style allows us to attribute this vase to an unknown artist of Lucanian origin: it is in ancient Lucania (a region which is located between present-day Calabria and Basilicata, in Southern Italy and between the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Ionian Sea, with Metaponto as a well-known city) that the first Italic style of red-figure painting developed.

13 - 24 of 3130 LOTS

.jpg)

.jpg)