Home > Auctions > 3 - 8 September 2024

Ancient Art, Antiquities, Natural History & Coins

Auction Highlights:

From a central London ADA dealership, 1980-1990.

Flowers were symbolic of rebirth due to the daily reopening of their petals after nightfall. As a result, they were widely used in domestic settings, religious and funerary contexts, and as adornments. Similar rosette discs, like those recovered from the Ramesside Period palace at Qantir, were used as decorative elements in royal palaces.

From an early 20th century collection.

Cf. Andrews, C., Amulets of Ancient Egypt, London, 1994, pp.62-3.

Small fly amulets first appeared in burials during the Naqada II Period, c. 3200 B.C. These amulets grew in popularity and the materials used to make them expanded during the New Kingdom. They are crafted from a variety of materials such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, carnelian, amethyst, faience, and bone. These amulets were thought to protect against insect bites and to ward off troublesome flying creatures through apotropaic magic. Some believe they may have even been intended to symbolise the fly’s fecundity. Additionally, pharaohs would bestow gold fly-shaped pendants as military awards to honour the bravery and fly-like persistence of soldiers in battle.

From the collection of a gentleman, acquired on the London art market in the 1990s.

Probably found Egypt, North Africa.

Acquired on the British art market.

From the collection of a South West London, UK, specialist Stone Age collector.

Ex Mariaud de Serres, Paris, France, 1990s.

From a London, UK, collection.

Cf. Manley, B., and Dodson, A., Life Everlasting. National Museum of Scotland Collection of Ancient Egyptian Coffins, Edinburgh, 2010, p.114, no.43, for a bead-work shroud incorporating the mask, winged scarab, and Four Sons of Horus.

Winged scarabs were often used as funerary amulets and believed to symbolise the deceased's rebirth and regeneration. The Four Sons of Horus were deities responsible for protecting the deceased's internal organs. Here, on the left, is the erect-eared jackal-headed Duamutef, who protects the stomach. Next is the falcon-headed Qebehsenuef, who protects the intestines. Then comes the human-headed Imsety, protector of the liver, and finally, the baboon-headed Hapy on the right, protector of the lungs.

From the collection of a North American priest.

Acquired between 1981-1996.

Property of a North American collector.

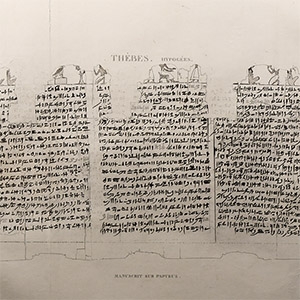

Cf. Description de l'Égypte publié par les ordres de Napoléon Bonaparte, Köln, 1994, pp.244-245.

Cf. Description de l'Égypte: ou recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l'expédition de l'armée française, publié par les ordres de Sa Majesté l'Empereur Napoléon le Grand, Antiquités, planches, tome deuxième, Paris, 1822, planche 69.

Produced between February 1802 and 1830 on the orders of Napoleon Bonaparte; published between 1809 and 1828. Just 1,000 copies were distributed to various institutions, printed on on laid paper with an 'Égypte ancienne et moderne' watermark. The book is subtitled Recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l’expédition de l’Armée française, publié par les ordres de Sa Majesté l’Empereur Napoléon le Grand (Gathering of observations and discoveries which were made in Egypt during the expedition of the French army, published on the orders of His Majesty the Emperor Napoleon the Great). It was the world's first encyclopedia devoted exclusively to the remains of ancient Egypt. The plates of this book are the first to present the archaeological sites of Thebes (Luxor). The papyrus manuscript was recovered from the underground chambers (hypogea). The papyrus is now in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Ex Yorkshire, UK, collection, 1960s-1980s.

Cf. Loffet, H.C., La Collection Emmacha: Antiquités Égyptiennes 2 – Objets divers, Paris, 2013, pp.84-7 no.105, for a stone baboon with a similarly elaborate decorated collar; Bartman, E., The Ince Blundell Collection of Classical Sculpture Volume III. The Ideal Sculpture, Liverpool, 2017, pp.185-6, pl.162a, for a baboon statuette with less stylised rendering.

The baboon was considered an embodiment of the god Thoth. The animal was associated with both the sun and the moon, often depicted wearing a moon and crescent headgear. Together, these aspects symbolised the cycle of rebirth, as it was believed that the deceased travelled through the night and was reborn at dawn. Thoth was highly regarded for his connection to knowledge, healing, and writing. Scribes would wear a Thoth baboon amulet to ensure continued professional success. In the Roman era, Thoth became the 'primary pseudonymous authority for diverse priestly texts' (Frankfurter, D., Religion in Roman Egypt,New Jersey, 1998, p.240). As some religious centres with animal cults were maintained in the Roman Period, it is possible that this figurine was a votive offering to the god. Baboon figurines have also been discovered in Isis sanctuaries in Rome. This discovery may indicate the mythological connection between the two deities, as Thoth provides words to Isis, enabling her to revive her husband, Osiris.

From an early 20th century Home Counties, UK, collection.

Ex H.M. Barker.

Private collection, England.

From an early 20th century Home Counties, UK, collection.

Cf. Manley, B., and Dodson, A., Life Everlasting. National Museum of Scotland Collection of Ancient Egyptian Coffins, Edinburgh, 2010, p.114, no.43, for a bead-work shroud incorporating the winged scarab and Four Sons of Horus.

These elements would have been placed on the chest and body below a beadwork mummy mask. Winged scarabs were often used as funerary amulets and believed to symbolise the deceased's rebirth and regeneration. The Four Sons of Horus protected the deceased's internal organs. Here, on the left, is the erect-eared jackal-headed Duamutef who protects the stomach, followed by the falcon-headed Qebehsenuef, who protects the intestines, then the human-headed Imsety, protector of the liver and, finally, the baboon-headed Hapy on the right, protector of the lungs.

From an early 20th century Home Counties, UK, collection.

The scarab, which represented the dung beetle, was the most popular amulet in ancient Egypt for approximately two thousand years until the Ptolemaic Period when it gradually fell out of favour. The popularity of scarabs extended beyond the borders of Egypt, and they were also distributed and produced in other regions, such as Phoenicia and Israel. The beetle is named khepri, derived from the verb 'to come into existence', and was considered the embodiment of the creator god Khepri, who was self-engendered. The ancient Egyptians mistakenly believed that the young beetle emerging from the dung ball was the result of an act of self-creation.

Ex London, UK, collection, 1990s.

325 - 336 of 3369 LOTS

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)