Home > Auctions > 4 June - 8 June 2024

Ancient Art, Antiquities, Natural History & Coins

Auction Highlights:

From the collection of Doctor Girard, a collector for over 60 years.

with Hotel des Ventes de Clermont-Ferrand, 22 May 2017.

Property of a French collector.

Cf. Tinius, I., Altägypten in Braunschweig. Die Sammlungen des Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museums und des Städtischen Museums, Wiesbaden, 2011, p.166, no. 322, for similar.

The djed pillar signifies the concepts of 'enduring' and 'stability' and was a common funerary amulet from the Old Kingdom onwards. It was first associated with the gods Ptah and Sokar but later became a symbol of Osiris, representing the god's backbone. In this context, the djed pillar appears in Chapter 155 of the Book of the Dead, concerned with the deceased's resurrection.

From an early 20th century collection.

Considering Egyptian artists often depicted fly whisks in the hands of pharaohs and high officials, one might assume that flies were simply a nuisance. However, the Egyptians held flies in high regard due to their quick speed, reactions, and persistence. Small fly amulets were made from various materials, including gold, silver, lapis lazuli, carnelian, amethyst, faience, and bone. They were believed to protect against insect bites and ward off flying creatures through apotropaic magic. Additionally, the pharaoh would give gold fly-shaped pendants as military awards to recognise the bravery and persistence of soldiers in battle.

From the collection of Doctor Girard, a collector for over 60 years.

with Hotel des Ventes de Clermont-Ferrand, 22 May 2017.

Property of a French collector.

Cf. Andrews, C., Amulets of Ancient Egypt, London, 1994, pl.28(a).

Various gods were depicted in the form of rams. The downturned horns on this amulet indicate that the ram is a representation of Amun. The ram was symbolically linked to concepts of revival and fecundity. Eventually, it became associated with Osiris and was recognised as the god's soul or ba.

From an early 20th century collection.

Cf. Petrie, W.M.F., Amulets. Illustrated by the Egyptian Collection in University College, London, 1914, pl. XLIII, no.257b, for a similar open-mouthed fish amulet.

Fish amulets were worn by young women and children, often at the end of a plait of hair, to guard against the risk of drowning.

Acquired before 1979.

From the private collection of Mr F. A., South Kensington, London, UK; thence by descent 2014.

Cf. similar specimens in faience at the Worchester Art Museum, inventory no.1925.539.

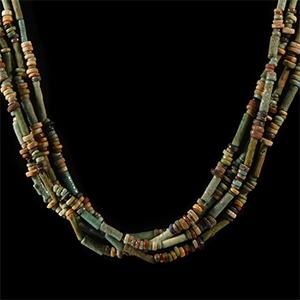

For thousands of years, artisans in Egypt created vibrant ceramics to echo the beauty of rare jewels. These ornaments were created with almost every material, colour and texture imaginable and they come from across Egypt and beyond: vibrant blue lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, glossy black obsidian from Turkey, and aqua-green turquoise from the Sinai. They were worn in life and, after death, they served as precious ornamentation for mummies.

Private collection, UK; acquired prior to 2013.

From an old English deceased estate.

Acquired on the London art market in the early 1990s.

Property of a London, UK, collector.

From an early 20th century collection.

Cf. Ben-Tor, D., The Scarab: A Reflection of Ancient Egypt, Tel Aviv, 1993, p. 77, no. 13, for similar.

Acquired on the German art market, 1989-1995.

with The Museum Gallery, 19 Bury Place, London, WC1A 2JB, 1998-2003.

Property of a London based academic, 2003-present.

Cf. Shatil, A., ‘Bone figurines of the early Islamic period: the so called “Coptic dolls” from Palestine and Egypt’ in Vitezović, S. (ed), Close to the Bone: current studies in bone technologies, Belgrade, 2016, figs.1,2,3, and especially 5 no.12, for the type.

In the late Roman Egypt or early Islamic period (7th–11th century A.D.) a new type of figurine appeared in the archaeological record: small, crudely crafted human figures made of bone. Some researchers considered them as toys meant to prepare girls for motherhood; others saw them as fertility figurines. They are mostly referred to as early Christian or “Coptic dolls”. In Egypt and Palestine they seem to appear suddenly in the 7th century, coinciding with the Arab conquests, but they might have existed earlier. With the new Muslim empire bridging former Roman and Sassanian lands, these dolls found their way to Egypt and Palestine where they were reproduced in huge numbers, becoming popular in all levels of society of the 8th and 9th century. By the end of the 11th century they disappeared as quickly as they appeared, probably because of restrictions placed on their production by Islamic laws.

From the old Belfort collection, expert Jean Roudillon.

Ex Hotel des Ventes de Belfort.

Property of a French collector.

Cf. Petrie, W.M.F., Scarabs and Cylinders with Names, London, 1917, XLIV, no.2, for this type of block bead with faintly impressed hieroglyphs.

From a late Japanese specialist collector, 1970-2000s.

From the private collection of the late Mrs Belinda Ellison, a long time member of the Egyptian Exploration Society, c.1940-2020.

325 - 336 of 2809 LOTS

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)