Home > Auctions > 5 - 9 December 2023

Ancient Art, Antiquities, Natural History & Coins

Auction Highlights:

From the collection of a prominent dealer of Islamic antiquities, Mr A.C., since 1980s.

From a late Japanese specialist collector, 1970-2000s.

Cf. Cambon, P., Hidden Afghanistan, Amsterdam, 2007, pp.155ff, for turquoise jewellery and garment appliques.

A great number of turquoise jewellery was employed by the Kushans, as shown by the marvellous finds of Tillya Tepe. In grave I the remains of a noblewoman show complex garment decoration, making use of bracteates, including triangles of gold with a granulated finish, double lozenges in turquoise, lapis lazuli and pyrites, and a square bracteate with turquoise inlaid work.

Acquired 1980-2015.

Ex Abelita family collection.

UK gallery, early 2000s.

UK gallery, early 2000s.

Acquired 1970s-1996.

Property of a North American collector, collection no.073.

London collection, 2016.

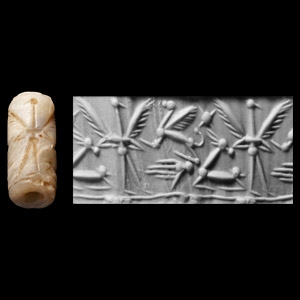

Cf. Teissier, B., Ancient Near Eastern Cylinder Seals in the Marcopoli Collection, Berkeley, 1984, item 21, for type.

Ex S Collection, London, UK, 1970-1990s.

Accompanied by a typed scholarly note signed by Professor Wilfrid George Lambert FBA (1926-2011), historian, archaeologist, and specialist in Assyriology and Near Eastern archaeology, in the late 1980s and early 1990s with reference no.V-619.

Acquired London art market, 1960s-1980s.

Ex property of a Hertfordshire, UK collector.

Acquired on the UK art market in 2016.

Property of a Kent lady collector.

From the collection of a West London businessman, formed in the late 1980s-early 1990s.

Property of an important West London collector.

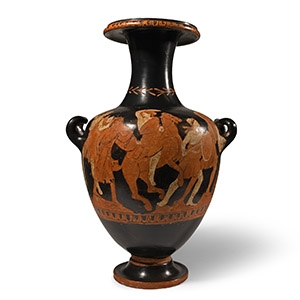

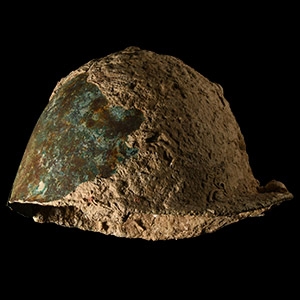

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Accompanied by a metallurgic analytical report, written by metallurgist Dr Brian Gilmour of the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, report number 618/129067.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.11982-209461.

See Rawlinson, G.M.A., The five great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World, III vol., New York, 1881; Schmidt, E.F., Persepolis II, Contents of the Treasures and other discoveries, Chicago, 1957; Soudavar, A., Iranian complexities, a study in Achaemenid, Avestan and Sassanian controversies, Houston, 1999; Garrison, M., 'Notes on a boar hunt (PFS 2323) in Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies vol. 54, No. 2 (2011), pp.17-20; Muscarella, O.W., Archaeology, Artifacts and Antiquities of the Ancient Near East, Boston, 2013.

Our specimen is a well preserved decorative votive plaque of Early Achaemenid age, although some elements could suggest the plaque as belonging to the late Elamite period. Usually these plaques are rectangular in shape and contain one or more figures. One of the predominant figures is the lion, an old symbol of power in Ancient Mesopotamia. It appears often in a similar form, for example in the Achaemenid seals (Schmidt, 1957, pp.42-44), as a hunter. The king of the beasts was considered a worthy foe, but sometimes was used as a symbol of the dynasty. Boars are also visible in seal patterns (Rawlinson, 1881, p. 240; Schmidt, 1957, pp.12,15,40,41,49). The rosette motif is well known in the Achaemenid art, like on Miho's Artaxerxes plate (Soudavar, 1999, p.11) or in decorated architectural fragments left on the ground in Persepolis (Soudavar, 1999, p.20 fig.14), and, more important, in the famous Otane's plaque (Soudavar, 1999, p.29 fig.32; p. 42 fig. 41a-b-c) or on the plaque reporting the Behistun text (Soudavar, 1999, p. 56 fig. 45). The rosette is a representation of solar emblems, and it is already visible in works of the first millennium B.C. (Muscarella, 2013, pp. 682-683, 781), and on the diadems of the Elamite rulers represented in the Achaemenid art. The representation of the Anshānite sun flower under a rosette vary in shapes and it is not always clear whether it predates the Darian Persepolitan style. Here, the presence of convex more than concave rosettes points more to a date anterior to Darius' kingdom (522-486 B.C.). The representation of the snakes is singular, considering that there is a general negativity in the Persian ancient culture associated with the word (snake) and the animosity that Zoroastrianism developed towards snakes. However, according to the Shāhnāmeh, the discovery of fire was ushered by the appearance of a magical snake, at which the legendary king Hushang threw a stone; it missed its mark but hit another stone and produced sparks that lit a fire. The Achaemenid Empire dominated the Near East and the eastern Mediterranean for about two centuries, from the mid-sixth to the mid-fourth BC, when it was conquered by Alexander the Great and the last Persian king, Darius III Codomannus, was killed by his generals. It was one of the largest empires in the world and in many ways one of the most successful. Votive plaques were dedicatory offerings in the temple, like a modern ex-voto. The motive of the boar hunt in Achaemenid art is visible on seals, and represents the warriors (lions) hunting the enemy (ibex, boar), a typical war-training exercise for soldiers, commanders and princes. The theme of the boar hunt by Persian warriors has traditionally been associated closely with later Achaemenid glyptic from the western realms of the empire, but in this ancient plaque representation the lions appear symbolically replacing the warriors.

Acquired 1970s-1996.

Property of a North American collector, collection no.043.

London collection, 2016.

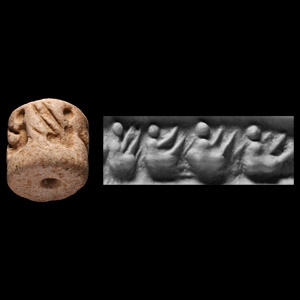

See Collon, D., Near Eastern Seals, London, 1990, for discussion.

Acquired 1970s-1996.

Property of a North American collector, collection no.047.

London collection, 2016.

Cf. Teissier, B., Ancient Near Eastern Cylinder Seals in the Marcopoli Collection, Berkeley, 1984, item 4, for type.

Acquired before 1990s/early 2000s.

From the family collection of Jack Lyttle (1944-2023), Kilmacolm, Scotland; thence by descent to his granddaughter.

Property of an East Sussex, UK, gentleman.

757 - 768 of 2409 LOTS

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)