Home > Auctions > 5 - 9 September 2023

Ancient Art, Antiquities, Natural History & Coins

Auction Highlights:

Acquired in the 1960s.

Ex private collection, Switzerland, thence by descent in 1996.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.11780-205646.

Cf. Born, H., Seidl, U., Schutzwaffen aus Assyrien und Urartu, Sammlung Axel Guttmann, Mainz, 1995; Brereton, G., 'I am Ashurbanipal, king of the world, king of Assyria', catalogue of the exhibition, London, 2018, p.146, no.155; for an example of the presence of a bucket in Urartian decorative arts and a similar depiction of Assyrian eagle-headed demon, see Aruz, J., Graff S. B. and Rakic Y. (eds.), Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age, New York, 2014, pp.89, 91-92 fig.2.17, cat.no.35a; for examples of the similarities between the Assyrian apkallu and Urartian spirits and deities, see two wall reliefs from Nimrud at the British Museum (inv. nos. 124561 & 102487).

These pieces of horse armour, destined to be the lateral protection for horses, were usually fixed at the four corners of the yoke (Connolly, 1986, p.17). Sometimes these side pendants provided protection for the upper part of horse's legs. Drawings and reconstructions of an Urartian chariot compiled from archaeological evidence shows the likely positioning on the shoulder of the horse (Gorelik, 1995, p.4). They served to protect the horse and also as symbols of divine protection. Similar pieces are visible on Assyrian reliefs (Born-Seidl, 1995, figs.53-54, relief from Nimrod; 62, from Assur; Curtis, 2013, pl.LXXV; Dezső, 2012, pl.12-13).

Ex Axel Guttmann collection.

Cf. Esayan, S.A., Gürtelbleche der Älteren Eisenzeit in Armenien in Beiträge zur allgemeinen und vergleichenden Archäologie, vol.6, pp.97-198, pls. 8 & 25, nos.25 and 26 (belts from Golovino).

Acquired 1971-1972.

From the collection of the vendor's father.

Property of a London, UK, collector.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.11752-202771.

Cf. Beglova, E.A., Antichnoe nasledie Kubani (Ancient heritage of Kuban) III, Moscow, pp.410-422 (in Russian); Dedjulkin A. V., 'Locally Made Protective Equipment of the Population of North-Western Caucasus in the Hellenistic Period', in Stratum Plus, no.3, 2014, pp.169-184; Симоненко А. В., 'Шлемы сарматского времени из Восточной Европы' (Sarmatian Age Helmets from Eastern Europe), in Stratum Plus, no.4, 2014, fig.15, no.1.

According both to Symonenko and Dedjulkin (2014, p.189, fig.9, nn.4-5-6), this category of helmets derived from the Chalcidian type with elements of pseudo-Illyrian variants. Like the Chalcidian helmets, our specimen shows vertical decorative lines on the bowl and the triangular brow decoration which characterises similar specimens.

Dr. T.J. Arne, Sweden, 1934.

Private collection, Sweden, late 1930s.

with Stockholm Auktionsverk, Stockholm, Sweden, 9 June 2014, lot 2613.

Cf. Christie's, The Axel Guttmann Collection of Ancient Arms and Armour, part 1, London, 2002, p.34, no.31.

This tanged bronze blade from Luristan belongs to a category of Luristan swords still in use in the Achaemenid Period, as proved from a blade with a perished handle (probably bone or wood) of the same type, in the National Museum of Iran (2694/15633). Examples without inscriptions like our model have been classified by Grotkamp-Schepers in the Solingen Museum as pieces from Luristan.

From the private collection of a London gentleman, from his grandfather's collection formed before the early 1970s.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.11819-206855.

See Behmer, E., Das zweischneidige Schwert der germanischen Völkerwanderungszeit, Stockholm, 1939; Lebedinsky, I., Armes et guerriers barbares au temps des grandes invasions, Paris, 2001; Lebedinsky, I., De l’epée scythe au sabre mongol, Paris, 2008, pp.114ff.

The sword belongs to the group of blades with wide guard coming from Eastern Europe, in particular from the regions of the Black Sea. The most striking examples are the sword of Dmytrivka (in the Zaporizhzhia), from a Hunnic grave, the guard and its extending reinforcement collar inlaid with precious stones; the sword of Lermontovskaia (North of Caucasus), from the grave of an Alan warrior (5th century A.D.), having the guard inlaid with coloured glass; the Pokrovsk-Voskhod swords (Region of Saratovo, on the Volga), from a Nomad grave of 5th century A.D., with garnet cloisonné on a gold background (Lebedinsky, 2001,pp.121ff.).

Private collection formed in Europe in the 1980s.

Westminster collection, central London, UK.

Accompanied by a copy of a four page report written by Saxon and Viking specialist Stephen Pollington.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.11878-206842.

See Sedov, B.B., Finno-Ugri i Balti v Epokhi Srednevekovija, Moscow, 1987, pl.V (20), for type; Salin, B., Die Altgermanische Thierornamentik, Stockholm, 1935.

The style of the design inlaid to the axe is interesting since it evidently owes a great deal to the kinds of Insular Style ornament found in manuscripts of the 8th century in the British Isles. The elegant curves of the narrow tendrils are strongly reminiscent of the zoomorphic elements found in the Lindisfarne Gospels, St Gall Codex and the Book of Kells (Salin, 1935, pp.342-3; Moss, 2018) and the inlaid designs show the characteristic parallel curves found for example on some of the initials in those documents. The tight knot serpentine bodies recalls the similar dense knot found in the Kells manuscript (Salin's figure 731). However, the details of the layout and execution show that the piece is unlikely to have originated in the British Isles.

Private collection formed in Europe in the 1980s.

Westminster collection, central London, UK.

Cf. The British Museum, museum number 1881,0623.1, for a similar knife.

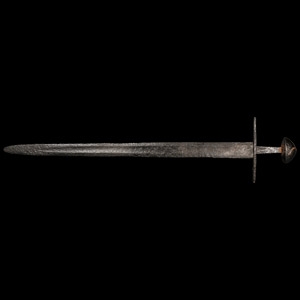

From the private collection of a London gentleman, from his grandfather's collection formed before the early 1970s.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.11821-206859.

See Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; Żabiński, G., ‘Viking Age Swords from Scotland’, in Acta Militaria Mediaevalia III, Kraków, Sanok, 2007, pp.29–84; see a sword in the Musée de l’Armée published by Peirce (2002, pp.70-71), for a similar pommel; cf. Paulsen, P., Schwertortbänder der Wikingerzeit, Stuttgart, 1953, for the chape; see also Michalak, A., Socha, K., ‘A sword scabbard chape with a depiction of a bird of prey from the surroundings of Kostrzyn’ in Slavia Antiqua, 2017, LVIII, pp.159-174, figs.3-4.

The blade of the sword is very similar to Petersen Type K; the hilt is a typical Type K, but having seven rather than five lobes to the pommel. The chape, the parallels of which are mostly of late 10th and early 11th centuries, is probably a later addition, possibly reworked to be fitted to the sword.

Otto Kruetz collection, Germany 1980s.

Belgium collection.

UK collection, 2000s.

Property of an East Sussex, UK, teacher.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

See Petersen, J., De Norske Vikingsverd, Oslo, 1919; Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002.

It is the decoration and the structure of the sword that suggests classifying it as Petersen Type K, with a similar structure to the famous sword from Ballinderry Bog (Peirce, 2002, pp.63ff.). Other examples of the type are the 9th century sword of Kilmainham, in Dublin, the Ostby farm sword from Oslo, a sword in the Musée de l’Armée, Paris, and the Kilde farm sword from Oslo, the fullers of which are very similar to our model (Peirce, 2002, pp.66-73).

From the private collection of a London gentleman, from his grandfather's collection formed before the early 1970s.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.11816-206858.

Cf. Petersen, J., De Norske Vikingsverd, Oslo, 1919; Oakeshott, R.E., The Archaeology of the weapons, London, 1960; Wilson, D. M., ‘Some neglected Late Anglo-Saxon swords’, in Medieval Archaeology, 1965, 9 (1), pp.32-54; Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; Żabiński, G., ‘Viking Age Swords from Scotland’, in Acta Militaria Mediaevalia III, Kraków, Sanok, 2007, pp.29-84; the sword finds good parallels in various similar Viking age specimens: a sword in the Bergen Museum (no.2605), a sword at the British Museum (1912, 7-23 1), a sword in the Musée de l’Armée, Paris (JPO2262), all published by Peirce (2002, pl.II, pp.74-76); also the Wensley hilt sword belongs to this classification (Wilson,1965, pp.42ff., pl.VIIa); another occasional find of this typology has been excavated in Wales in 2004, a chance discovery in the garden at Hawarden (NWM inv. 2007.4H).

This sword shows evidence of beautiful pattern-welding. The great curvature of the hilt, stronger than any other type of Viking swords, characterises the typology of L swords. This is clearly visible on the specimens from Dolven and Nedre (Stokke) published by Petersen (1919, figs.94-95).

Ing Peter Till collection, Austria 1990s.

UK collection, 2000s.

Property of an East Sussex, UK, teacher.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

Cf. Oakeshott, J.R.E., The Archaeology of the weapons, London, 1960; Peirce, I., Swords of the Viking Age, Suffolk, 2002; Nicolle, D., Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050-1350, vol I, London, 1999; the sword finds a good parallel with a specimen from Spain, published by Peirce (2002, p.124); with a sword dated to circa 1200, from Germany, preserved in the Wallace collection, London, England (Nicolle, 1999, fig.424); with a sword from Dresden, with the name INGELRII on one side and the phrase HOMO DEI on the other, dated to about 1100; also with a sword once in the Oakeshott collection with the mark of Carrocium, dated to around the 11th century.

The sword is of Oakeshott Type Xa or XI and Petersen Type X. According to Oakeshott (1960, p.204) the swords of type X were a development of Viking sword type VIII with slight modifications. Oakeshott describes such swords as common in the late Viking age (late 10th century) and remaining in use until the first quarter of the 13th century.

From the private collection of a London gentleman, from his grandfather's collection formed before the early 1970s.

See Oakeshott, R.E., The Archaeology of the weapons, London, 1960; Oakeshott, E., The sword in the Age of the Chivalry, Woodbridge, 1964 (1994); Oakeshott, E., Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991; Oakeshott, E., Sword in hand, London, 2001 (2007); similar specimen in Oakeshott, 1991, p.187, sword formerly in the collection D’Acre Edwards, now on loan to the Royal Armouries (pommel T.5, facetted and cross-style of type 4).

This magnificent example was well-suited to a cut-and-thrust style of fighting, a logical development of the Oakeshott XVI typology. This is mainly visible in the specimens of typology XVIIIb, typical of English effigies and brasses between 1370-1425. Because the previous types of swords were practically useless against the fully armoured man-at-arms, Western European warfare needed a sword capable of piercing the weak points of the enemy's protective equipment, leading to the development of types XV, XVI and XVII, and eventually of type XVIII. The subtypes XVIIIa and b had a longer blade, and type XVIIIb was a very long-gripped bastard sword. This word (often referred to as ‘hand-and-a-half sword’) was applied through the late Middle Ages to the long-gripped weapons. Marc de Vulson, writing on the occasion of a duel fought in 1549 before Henry II of France, stated 'Deux epées bâtardes, pouvant servir à une main ou à deux' (two bastard swords able to serve with one hand or with two).

133 - 144 of 2453 LOTS

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)