Home > Auctions > 23 - 27 May 2023

Ancient Art, Antiquities, Natural History & Coins

Auction Highlights:

Ex Sangiorgi collection, acquired in the 19th century.

with Christie's, 3 June 1999, lot 121.

The remains of a 19th/early 20th century label can be seen on the glass on one side.

with Christie's, New York, 9 December 1999, lot 476.

American private collection, Westchester, New York, acquired in 1999.

with Bonhams, London, 30 September 2015, lot 91.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.203222.

Cf. The Metropolitan Museum, New York, accession number 81.10.8, for similar; cf. a very similar example with lid, discovered in the Conjunto Arqueológico de Carmona, Carmona (Sevilla), Spain, in Boletín del Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid, IX,1991, figs.1-14; cf. The British Museum, museum number 1993,0102.11, for similar; cf. The Corning Museum of Glass, accession number 70.1.44, for similar. cf. also Metropolitan Museum of Art Twelfth Annual Report of the Trustees of the Association for eight months ending December 31, New York, 1881, pp.215-216.

A similar jar in the British Museum was found in Warwick Square, London, inside a lead canister, and was originally filled with bone ashes. The Romans often re-used glass jars, originally made for storing liquids and foodstuffs, as cremation vessels, but this kind of jar seems too fragile and was therefore probably purpose-made. The lead canister, which was found with the jar from London, protected the glass and bones. Georgio Sangiorgi is one of the most famous names associated with the field of ancient glass collecting. Working from the Galleria Sangiorgi in the Palazzo Borghese, Sangiorgi acquired the most magnificent collection of ancient glass, seeking only the finest examples.

Private collection, Rosenheim, Germany, 1960s.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.11734-201200.

Cf. similar oinochoe in Sotheby’s, Antiquities and Islamic Art, New York, 12 December 1997, New York, 1997, lot 133; Tassinari, S., La vaiselle de bronze, Romaine et Provinciale, au musée des antiquités nationales, Paris, 1975, figs.152-153, for similar typologies with different decoration; cf. also Radnoti, A., ‘Eine Bronzekanne aus Augsburg’ in Bayerische Vorgeschichtblätter, 25, 1960, pp.99-124, and pl.7; Nuber, H.U., Kanne und Griffschale, Ihr Gebrauch im täglichen Leben und die Beigabe in Gräbern der römischen Kaiserzeit in 53.Bericht des Römisch-germanischen Kommission, Berlin, 1972.

Considering the primary function of oinochoe as drinking jugs, the images decorating them were often related to the god of wine, Bacchus, here probably represented as young Dionysus accompanied by a lion.

From a Cambridgeshire, UK, collection, 1990s.

This brooch is an extreme rarity and is believed to be the finest known example.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.11747-202502.

Cf. Hattatt, R., Ancient and Romano-British Brooches, Sherborne, 1982, p.147, no.140; for the Hadrian’s coin see Mattingly, Roman Coins from the earliest times to the fall of the Western Empire, London, 1977, pl.XXXIX, 25 (BM inventory no.1672).

These brooches were a mystery until one was excavated at Wiggonholt, Sussex, together with three other damaged specimens now in the Devizes Museum, all from Wiltshire (more precisely Cold Kitchen Hill). The image of the original coin was slightly modified. The local craftsman improved the coin type making his brooch more interesting, transforming the Emperor Hadrian on horseback into two cavalrymen, probably the sacred Dioscuri, while the Roman Aquila, symbol of the legions, was taken from the top of the signa and placed in the foreground.

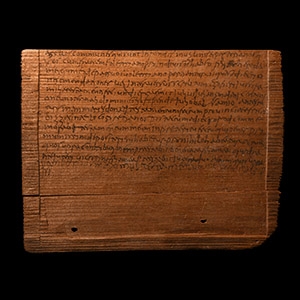

From an important London collection since 1975.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by searcher certificate no. 200269.

See Thomas, J. D., Vindolanda: The Latin Writing Tablets, Britannia Monograph Series No 4, London, 1983, for examples of wooden tabulae re-used as writing surfaces; for examples of testamentary documents on wooden tablets that have survived, see FIRA III, p.47, for Anthony Silvanus from 142 AD, also see BGU VII 1695 for Safinnius Herminus; for another from Transfynydd, North Wales, see Arch. Camb. 150, pp.143-156.

Rothenhoefer, P., Neue römische Rechtsdokumente aus dem Byzacena-Archiv / New Roman Legal Documents from the Byzacena Archive, (forthcoming).

The text is written in a very formulaic language typical of Roman legal-documents (among other things, familia testamenti faciundi erga emit Iul. Maianus: the entire possessions, in order to make a will, was bought by Iul. Maianus).

with a London, UK gallery 1971-early 2000s.

Acquired 1990s-early 2000s.

East Anglian private collection.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by searcher certificate no. 200925.

Cf. Walters, H.B., Silver / Catalogue of the Silver Plate (Greek, Etruscan And Roman) in the British Museum, London, 1921, no.146, for a similar elaborately decorated silver strainer fastened to a silver funnel by a hinge in the British Museum, inventory no.1890,0923.6.

Round-bowled strainers of various sizes occur in many late Roman hoards of domestic silver. They were used to strain the sediment from wine as it was poured into a drinking vessel. It is noteworthy that wine could have been a kind of gift from the Romans to the members of the foreign or provincial elite, often allies of the Roman leaders. Sets of bronze dishes (such as jars, scoops and strainers) along with glass horns (often with bronze fittings) and silver cups for drinking, usually placed in the so-called princely graves, confirm the wine consumption and indicate the area of its occurrence also outside the Empire.

German private collection, 1980s.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.201190.

Cf. similar bronze bowl in the collection of the British Museum, London, under accession no. 1939,1010.109.

Ex Gorny & Mosch 11th July 2006, auction 150, lot 543.

East Anglian private collection.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.199905.

The letter C likely represents the Roman numeral Centenarius, or 100 Roman lbs.

Ex Cambridgeshire, UK, collection, 1990s.

See various examples in PAS YORYM529; SF4761; NARC1285; KENT4759;BH-1DB7F2; NLM-8D8EF3.

The champlevé enamel of this toilette hanger is a clear example of provincial Roman decorative patterns. Such enamelled chatelaine brooches, with toilet sets affixed, were a common female accoutrement, notably in Roman Britain.

Acquired before the 1970s.

Ex J.L. collection, Surrey, U.K., thence by descent.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.203881.

Cf. Sommer, M., Die Gürtel und Gürtelbeschläge des 4. und 5. Jahrhunderts im römischen Reich, Bonner Hefte zur Vorgeschichte, 22, Bonn, 1980 (1984), pls.5, no.2; pl.12, nos.1-2; pl.38 no.4-5; 47 nos.3-6; 51, no.9; pl.69 nos.3-4.

Most precious military buckles, like this one, were reserved for soldiers belonging to Legiones Palatinae, i.e. the legions forming part of the imperial Comitatus, accompanying the emperor in his military expeditions.

Acquired before the 1970s.

Ex J.L. collection, Surrey, U.K., thence by descent.

Cf. Sommer, M., Die Gürtel und Gürtelbeschläge des 4. und 5. Jahrhunderts im römischen Reich, Bonner Hefte zur Vorgeschichte, 22, Bonn, 1980 (1984), pls.5, no.2; pl.12, nos.1-2; pl.38, no.4-5; 47, nos.3-6; 51, no.9; pl.69, nos.3-4.

Most precious military belts were reserved for soldiers belonging to Legiones Palatinae, i.e. the legions forming part of the imperial Comitatus, accompanying the emperor in his military expeditions.

Private collection, Rosenheim, Germany, 1960s.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D'Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.11732-201194.

Cf. Boube-Piccot, C., Les bronzes antiques de Maroc, III, Les chars et l’attelage, Rabata, 1980, p.199, no.333, from Banasa; cf. Wenedikov, I., Le char thrace, Sofia, 1960, pp.153-201, pl.97, and Gudea, N., Porolissum. Un complex arheologic daco-roman la marginea de nord a Imperiului roman. II. Vama romana (monografie arheologica). Contributii la cunoasterea sistemului vamal din provinciile dacice, Cluj-Napoca, 1996, fig.31 (also Boube-Piccot, 1980, fig.10bis); a similar sheath had been found with the chariot of Nicomedia, and a similar, with open lateral rings showing serpents have been found in Thrace: three with a chariot from the tumulus of Doukhowa-Moghila, four with a cart from Ljubimec (Wenedikov, 1960, pl.55A, fig.190-192; p.40, no.150, pl.30, fig.107), four with the cart from Svilengrad, and a single isolated find has been discovered in the Burgos region.

These chariot fittings were usually elements surmounting the axle, a sort of sheath allowing the suspension from the body of the cart to the wagon box using belts. The chariot (currus) which these fittings adorned may have been used for transporting wealthy and aristocratic individuals, although most probably it was a tensa, i.e. a triumphal chariot or a ceremonial vehicle upon which images and symbols of divinities were placed.

49 - 60 of 2508 LOTS

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

![English Milled Coins - George VI - 1937 - Cased RM Proof Coronation Gold Set [4] English Milled Coins - George VI - 1937 - Cased RM Proof Coronation Gold Set [4]](https://timelineauctions.com/upload/images/items/small/203351-s(2).jpg)

.jpg)