Home > Auctions > 23 - 27 May 2023

Ancient Art, Antiquities, Natural History & Coins

Auction Highlights:

Acquired in the 1960s.

Ex Bursnall collection, Leicestershire, UK.

From the collection of a North American gentleman.

Lewis, M. and Richardson, I., Inscribed Vervels, Oxford, 2019; Type B listed on pp.87-8 where dated c.1450-c.1600, with the note that it was previously sold by Timeline Auctions 2 December 2011, lot 793.

Unique and with links to royalty and the Wars of the Roses. Edmund Plantagenet, Earl of Rutland was executed after the Battle of Wakefield (probably by John Clifford) and was the son of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York (a great-grandson of Edward III, father of Edward IV and one of the most powerful English magnates during the Wars of the Roses between the Yorkists and Lancastrians). The first Earl of Rutland was Edmund Plantagenet (grandson of Edward III and executed following the Southampton Plot against Henry V), uncle to Richard. The Earldom of Rutland has historically been closely linked to the Duchy and House of York.

Ex Adalberto Frezza, 2006.

Ex central London gallery.

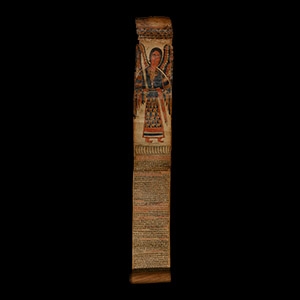

See Heldman, M., Munro-Hay Stuart, C., African Zion, The sacred art of Ethiopia, Yale University Press, 1993, pp.44, 65.

The sick looked upon such scrolls as it was believed that the images contained in them had healing powers. The scrolls were prepared by unordained clerics, or debatras, employed by Christian families, a practice which continued into the 20th century. Debatras were skilled at diagnosing the causes of illness, and treated them through scrolls such as that offered here, together with herbal and plant-based remedies; the images and prayers were believed to act on the spiritual source of the ailment, whilst the botanical remedies acted upon the physical symptoms. The scrolls covered the length of the afflicted person's body, providing preventative as well as curative protection and were often passed down through generations of the same family. The patients were often illiterate peasants, and the scrolls written in archaic Ge'ez, a liturgical language comprehended only by clerics; the debatras explained the prayers and the images to the sick. The images are designed to be mesmeric, the penetrating gaze of eyes from within the design giving them a sense of power.

Ex Adalberto Frezza, 2004.

Ex central London gallery.

See Mercier, J., Ethiopian Magic Scrolls, New York: George Braziller, 1979, for discussion.

Ex Cy Lester, an antiquarian bookseller, London, UK, circa 1990.

Ex central London gallery.

See similar image of dressed Saint George in Walters Gallery, Ethiopian Manuscript W835, folio 37.

Among the imagery of Ethiopian equestrian saints, three main representational categories can be distinguished: 1) simple portrait of the saint armed with spear or lance and holding the reins of a horse; 2) the saint spearing an enemy; 3) the saint according to one of the aforementioned types placed in a narrative scene.

with Setdart Subastas, 28 September 2022, lot 35276208.

Ex central London gallery.

with Boisgirard, 28 November 2013, lot 138.

Ex central London gallery.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.202063.

Cf. Brooklyn Museum, New York, inv.nos. 46.126.1 and 46.126.2, illustrated in New York, 2012, pp.72-3, nos.44A,B.

The shape and decorative scheme of these liturgical fans has existed since at least the 8th century A.D. These fans were likely crafted as souvenirs for pilgrims returning from Jerusalem, or for them to bring to Jerusalem as homage to the church. Seraphim are the highest-ranking angels in the traditional hierarchy, and as such are closest to God.

Found whilst searching with a metal detector on 11th June 2021 by Mr Graham Higgins, near Hatford, Oxfordshire, UK.

Accompanied by a copy of the report for HM Coroner by the Finds Liason Officer (FLO) for the British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) for Oxfordshire under Treasure reference number OXON-FBF56A.

Accompanied by a copy of the letter from HM Senior Coroner for Oxfordshire disclaiming the Crown's interest in the find.

Cf. The British Museum, museum number 1961,1202.385, for a similar design; cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, 1931, p.57, for a very similar inscription.

Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985.

Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK.

Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1542, for a similar skull on a ring of a similar date.

Ex Albert Ward collection, 1974-1985.

East Anglian private collection.

Cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, London, p.43, for this inscription; cf. The British Museum, museum numbers AF.1252 and AF.1253, for this inscription on a ring dated 17th-18th century AD, and museum number AF.1315 for this maker's mark, believed active between 1755-1764, name unknown; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, id. SUSS-73E152, for a similar ring with this inscription, also stamped 'JK', dated 1700-1800, possibly the same maker's mark.

In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty.

Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985.

Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK.

Cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record id. HAMP-CD6223, for another ring with this inscription and with an exterior design executed in similar style.

In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty.

Acquired on the UK antiques market between 1974-1985.

Albert Ward collection, Essex, UK.

Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1266, for a ring with this inscription dated 17th century; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record ids. WILT-AFE9A5, and GLO-D67CD3, for similar rings with very similar inscriptions dated 17th century; cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, 1931, p.46, for two very similar inscriptions.

In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty.

Found whilst searching with a metal detector on 28th March 2022 Mr Graham Higgins, near Hatford, Oxfordshire, UK.

Accompanied by a copy of the report for HM Coroner by the Finds Liason Officer (FLO) for the British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) for Oxfordshire under Treasure reference number OXON-FC03F7.

Accompanied by a copy of the letter from HM Senior Coroner for Oxfordshire disclaiming the Crown's interest in the find.

Cf. The British Museum, museum number AF.1339, for this inscription with slight spelling variation and for a similar plain exterior; cf. Evans, J., English Posies and Posy Rings, OUP, 1931, p.73, for this inscription with slight spelling variation; cf. The Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, record id. SUSS-04EA22, for a similar style of ring also heavy at 7.43 grams.

In the medieval period many rings bore posy inscriptions in Latin or French, the languages frequently spoken by the affluent elites. Later, inscriptions in English became more usual, although the lack of standardisation in spelling might surprise the modern reader. The inscription is generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer and most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from the popular literature of the time. In fact, love inscriptions often repeat each other, which suggests that goldsmiths used stock phrases. In the later 16th century, ‘posy’ specifically meant a short inscription. A posy is described in contemporary literature as a short ‘epigram’ of less than one verse. George Puttenham (1589) explained that these phrases were not only inscribed on finger rings, but also applied to arms and trenchers. The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the 16th century onwards, and continued until the late 18th century. Sources suggest that rings could be acquired ready- engraved, or alternatively engraved sometime after their initial production, by a hand other than the goldsmith’s. Joan Evans assumed that posy rings were principally used by/between lovers and distinguished four contexts for the giving of posy rings by one lover to another: betrothals, weddings, St Valentine’s Day and occasions of mourning. Samuel Pepys’ diary makes clear that posy rings might also mark the marriage of a family member, when bearers could even commission their own rings and chose their own mottoes from books. The rings could also function as tokens of friendship or loyalty.

253 - 264 of 2508 LOTS

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

![English Milled Coins - George VI - 1937 - Cased RM Proof Coronation Gold Set [4] English Milled Coins - George VI - 1937 - Cased RM Proof Coronation Gold Set [4]](https://timelineauctions.com/upload/images/items/small/203351-s(2).jpg)