Home > Auctions > 23 - 27 May 2023

Ancient Art, Antiquities, Natural History & Coins

Auction Highlights:

Ex Pierre-Richard Royer, 2010.

Ex central London gallery.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.202060.

Cf. Eagan, G., The Medieval Household: Daily Living c.1150-1450, MOLA, London, 2010, p.135, for similar.

with Ansorena, 10 November 2014, lot 456.

Ex central London gallery.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.11742-202064.

Cf. similar iconography in ‘The Head of Christ, probably 1500/1510’, woodcut at the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, German 15th Century, accession no.1943.3.521; the Copy of the Vera Icon of Van Eyck, in Koldeweij, A.M. & van Vlijmen, P.M.L. (ed.), Schatkamers uit het Zuiden, Rijksmuseum Het Catharijneconvent, Utrecht, 1985, pp.156-158.

The crimson tunic of our painting is clearly derived from the Van Eyck model, where crimson is associated with the Majesty of Christ. Christ is in fact shown here as the Saviour of the World (Salvator Mundi), a popular image in 15th century paintings.

Acquired 1990s-early 2000s.

East Anglian private collection.

Ex French private collection, 2000.

Ex central London gallery.

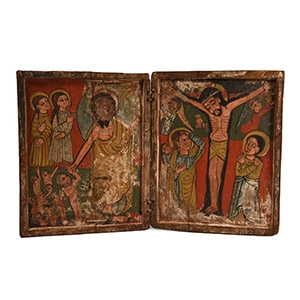

See Chojnacki, S., Major Themes in Ethiopian Painting, indigenous developments, the influence of foreign models and their adaptation, from the 13th to the 19th century, Wiesbaden, 1983, figs.39, 89, 90, 183, for similar Crucifixion and Resurrection scenes.

The icon shows the Western influence on Ethiopian art. The Crucifixion image contains many elements of this iconography which are found in many Oriental and Western Art of Middle Ages, but with significant changes from the previous representations: Jesus is nailed with three nails and not four, the head leaning towards his right shoulder and the hair falling on his shoulders. Following the Western influence, Christ is represented in a spasm of physical pain, and consequently a more detailed anatomy of his chest and abdomen is depicted. This concept of the Crucifixion, common in the Italian Late Middle Age and Renaissance art, found its way to Ethiopia at some time towards the end of the 15th century, or at the beginning of the 16th century. As in the majority of the Resurrection icons of this period, Christ is dressed in a long robe with a cloak or toga draped over one shoulder.

with Duran Arte y Subastas, 17 September 2015, lot 72.

Ex central London gallery.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate number no.11750-202070.

See Museo Nacional del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas, Museo del Prado, Madrid, 1985, p.634, for a painting of 'La Visitación', for similar style.

The painting represents the Virgin Mary Dolorosa or Our Lady of Seven Sorrows: a classic representation of the suffering experienced by the Virgin during the passion of Jesus Christ.

Ex J. Altounian collection (1890-1954), until 2009.

Ex central London gallery.

Ex old Swiss private collection.

Ex central London gallery.

Private collection, Paris.

Ex property of Ellen G and Manual E Rionda, Glen Goin, Alpine, New Jersey, U.S.A.

From the collection of Woody and Nancy Bolton, Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S.A.

with Samuel T. Freeman & Co, 22 May 2012, lot 263.

Ex central London gallery.

Private collection, Paris.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.202093.

See Marks, R., Stained Glass in England During the Middle Ages, London, 2014, for discussion.

with Thierry de Maigret, Vitraux et Dessins, Paris, 20 June 2014, lot 53.

Cf. Hayward, J., English and French Medieval Stained Glass in the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Corpus vitrearum, United States of America, 1, New York, revised edition 2003, pl.25/1.

with Piasa, 7 June 2013, lot 17.

Ex central London gallery.

Accompanied by an academic report by Dr Raffaele D’Amato.

This lot has been checked against the Interpol Database of stolen works of art and is accompanied by search certificate no.11738-202062.

Cf. Durliat, M., La Sculpture Romane de la Route de Saint Jacques, Dax, 1990, fig.295, p.293; Igarashi-Takeshita, M., ‘Les lions dans la sculpture romane en Poitou’ in Cahiers de civilisation médiévale, 23e année (n°89), Janvier-Mars 1980, pp.37-54, fig.8, pl.1.

The form of the capital and the shape of the beasts are similar to those sculptures that survive in churches on the pilgrimage route to Santiago da Compostela – namely in Southern France and Northern Spain, but the bodies of the lions have many correspondences with the capital sculptures of Poitou. The lions were considered to be guardians against evil and the image of the young boy is probably a representation of the prophet Daniel. There is a similar capital in the Church of d'Airvault (Deux-Sèvres) also ornamented with lions and a human head.

229 - 240 of 2508 LOTS

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

![English Milled Coins - George VI - 1937 - Cased RM Proof Coronation Gold Set [4] English Milled Coins - George VI - 1937 - Cased RM Proof Coronation Gold Set [4]](https://timelineauctions.com/upload/images/items/small/203351-s(2).jpg)

.jpg)